HRO 10: Blind Spots-What you don't know hurts a lot!

Introduction

Blind spots are safety vulnerabilities in a system or organization unknown to the management team so they remain uncorrected. Given the right triggers, they can lead to disaster. Blind spots are a deeper problem than ignorance, the things an organization doesn’t know. People in an organization can reduce their ignorance after recognizing a problem by collecting more data and analyzing it. A blind spot is a problem that people don’t recognize.

A blind spot can be two different things:

First, it can come from cognitive biases or be a deficiency in training, personal knowledge, processes, and equipment that is unknown or cannot be detected with an organization’s standard processes.

Second, it can be something that people don’t recognize, interpret, or distinguish as important. No action is taken because of values, norms, interruptions, and priorities that influence how people evaluate and interpret what they find. The signal presented doesn’t look like a warning until after the disaster. (Weick, 1980)

This means that a blind spot “can be a function of the situation or the observer” (Weick, 1980, p. 182), which suggests that reducing blind spots requires improved detection AND recognition processes.

Recognizing blind spots depends on the observer in complex ways. Sometimes, only experienced observers can recognize something out of place or an anomalous result. They have the experience to know what should happen and question why it didn’t. Other times, people with more experience can become inured to frequent problems (“Ignore that alarm. It always does that.”) and it is the newcomer that asks about it (“Why does that happen? I thought we were supposed to believe our indications.”).

* Weick, K. E. (1980). Blind spots in organizational theorizing. Group and Organization Studies, 5(2), 178–88.

Where do blind spots come from? One source is the equipment people use every day. Every technical design is based on assumptions made by the designers that can be opaque to operators until they push buttons in the wrong sequence. Another source is people. Psychologists have observed that people are more likely to notice what they expect. Unexpected outcomes tend to get ignored because they are not part of their everyday experiences (i.e., what they’ve seen before). This is confirmation bias (“believing is seeing”), one of many cognitive biases that contribute to blind spots. Others include: maintaining the status quo, group think, deferring to the person with seniority, incorrect framing (thinking you’re in one situation when you really are in another), and overconfidence.

The Dark Side of Commitment

In the day-to-day operations of any organization, people are committed to producing certain outputs consistently with high quality (if they want to stay employed). Commitment is good. It makes people more serious about the work they do and doing it well. People that aren’t committed to the goals of the organization or have their own agenda usually don’t last very long because they stand out as “problems.”

There is a dark side to commitment because it can lead to confirmation bias. It increases the tendency to ignore the weak signals that blind spots produce. Once a person becomes committed to an action or a goal, they build an explanation that justifies accomplishing it. Psychological research suggests that’s the normal order: act then justify. Commitment makes the explanation persist and transforms it into an assumption that a person takes for granted thereafter. Once this transformation has occurred, it is unlikely that the assumption will be reexamined, which makes it a potential contributor to a crisis (Weick, 1988).

* Weick, K. E. (1988). Enacted sensemaking in crisis situations. Journal of Management Studies, 25(4), 305-317.

The Paradox of Blind Spots

Blind spots exist, but like black swans, they can’t be found by looking for them. First, you don’t know where to look and second, you don’t have the resources to look “everywhere.” While formal problem reporting and resolution and independent audits are helpful, every organization has to balance the attention devoted to finding and resolving problems with the resources devoted to mission accomplishment. Some organizations make this balance easy: they don’t look for problems at all.

Blind spots are problems, but they often don’t look like problems before a system accident and subsequent hindsight-biased investigation. This is why accident investigations that focus on “missed signals” aren’t helpful. Blind spots don’t usually announce themselves with sirens and alarms. They emerge as weak signals that get missed in the course of doing normal work or are created during one task and discovered much later on another.

There are innumerable blind spots in organizations since the humans in an organization can’t know everything. Blind spots can’t be managed with standard organizational systems and problem resolution processes. These processes are designed for the problems people can imagine, but they can’t imagine everything. The key to blind spots isn’t to try managing them. It is to reduce the tendency to ignore them and take the time to assess their risk when you stumble into them.

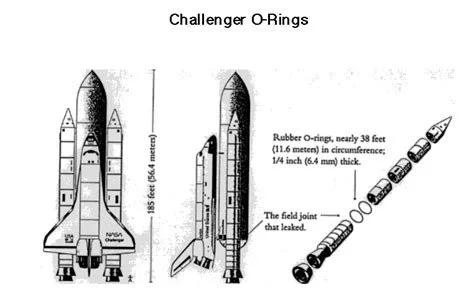

My next post is a case study of how blind spots surfaced during the Challenger launch decision of January 1986. It has been analyzed in many books and articles, but my post is unique because of its focus on blind spots.