HRO 11: Case Study-The Challenger Launch Decision

Background

In January 1986, the night before the Challenger Space Shuttle’s final launch, the solid rocket booster prime contractor, Morton-Thiokol (MT), recommended delaying the next day’s launch because of anticipated low temperatures at launch time. George Hardy, Director in charge of the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Boosters (SRB) for NASA, convened a conference call to get more information and analyze the problem.

The SRBs were copied from a prior, highly reliable design except the application, the forces, and the rocket size were totally different. They were a totally new design and the record of reliability of the prior design was not applicable. There was no way to test them in a realistic environment except on an actual Space Shuttle launch. NASA managers knew and accepted this risk because they believed they had sound technical reasons for doing so.

Blind Spots

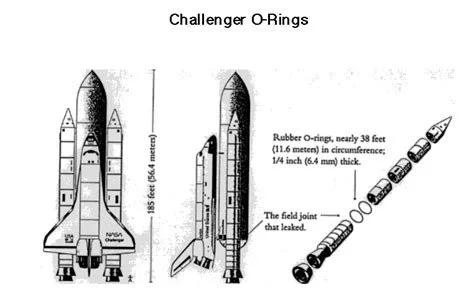

Years before January 1986, government engineers at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center wrote to the manager of the Solid Rocket Booster (SRB), George Hardy, more than once suggesting that MT’s joint design was inadequate. O-rings were used to prevent hot gasses from burning solid booster sections from igniting the external fuel tank. In one memo, a NASA engineer suggested that a gap in the primary O-ring would render the secondary O-ring useless. They were right, but this was not the generally accepted technical view at the time. Hardy did not forward these memos to MT, the SRB prime contractor, so didn’t require them to formally address the concern raised by the Marshall engineers. Blind Spot #1.

The recommendation in January 1986 from MT was to delay the launch until later in the day when the air temperature would be 40F. 40F is what MT engineers recommended as the lowest acceptable launch temperature. This was a surprise to NASA managers because they thought the launch temperature limit was 31F. There is no record before, during, or after the conference call of any conversation about why NASA had been launching shuttles for FIVE YEARS without a clear understanding of the low-temperature limit for launch. Blind Spot #2.

Hardy started the conference call by invoking NASA’s Flight Readiness Review (FRR) rules. The purpose of the FRR was to prove it was SAFE to launch. Hardy’s decision to invoke FRR protocols put MT in the position of having to prove, with data and sound technical rationale (the standards of FRR), that it was UNSAFE to launch. This was a framing decision that was unrecognized at the time: the FRR rules were not suited for the unique situation of MT’s recommendation not to launch. Blind Spot #3.

After very passionate and stressful conversations during the conference call, MT engineers requested to “go dark” (mute their conversation) to caucus among themselves. When they came back on the line, they recommended proceeding with the launch as scheduled. NASA managers didn’t know why they changed their recommendation or that some members of the MT team didn’t agree with the recommendation. They didn’t ask. Blind Spot #4.

What I have called blind spots in this abbreviated case study share two key characteristics:

None of the senior leaders at NASA knew about them before they surfaced.

When they surfaced, they weren’t what people could easily recognize as abnormal conditions (i.e., something that needed to be fixed, a rule violation, or a parameter out of specification).

Alas, sometimes the relevance of one fact among hundreds in a particular setting can only be determined after you lose a Space Shuttle and its crew (Perrow, 1981).

* Perrow, C. (1981). Normal accident at three mile island. Society, 18(5), 17-26.

Final Thoughts

My purpose in using the Challenger launch decision to illustrate blind spots wasn’t to fault the participants. There is nothing really exceptional about the blind spots I chose and the way they came up could happen in any organization. They reflect real people doing real work in a world of deadlines, high stakes, competing priorities, and uncertainty. Calling attention to them in this case shows how blind spots present themselves quietly, indirectly, and with feelings of “Gee, I wonder why that is?” when people are focused on what look like more important things. At the moment they surface, blind spots never look important.

You have almost no control over when, where, and how blind spots appear. How could you? You aren’t looking for them and you have stuff to get done. Often, the pressure of the other things that need to get done cause the blind spot to quickly submerge into a sea of background noise. You might be present during a very important conference call, but are you going to interrupt a senior manager and tell him he’s wrong? You just move on.

You have some influence over how you respond to the little voice when you hear, “That’s odd. I wonder why that happened?” Someone might say it aloud (very rare) or you might only hear it in your head. What you can do when hear this is the topic of my next post.