HRO 12: Close Encounters with Blind Spots

Introduction

Recognizing and responding to blind spots in safety critical systems and operations are more than good ideas for HRO. They are essential for correcting weaknesses in the safety system. Rules, policies, and training are necessary, but not sufficient. People in every role and at every level of the organization have blind spots.

In my previous post on organizational blind spots, I emphasized three things: every organization has them, you can’t search for them directly because you don’t know where to look, and many organizations don’t react well when they discover them. In this post, I suggest some ways to encounter blind spots more frequently and improve how people in your organization react when they notice “something’s not quite right.”

How Blind Spots Emerge

Blind spots surface in the course of doing work, but they aren’t accompanied by warning lights as I noted in my prior post. There are two important ways that blind spots can present themselves. The first is through abnormal conditions and anomalies that people encounter while working. Abnormal conditions are usually well-defined in organizations that are disciplined about seeking higher reliability. For example, something lacking in a procedure (a missing step, signature, or piece of equipment), a service that is not available when needed, equipment that gives constant error messages, or someone not responding when called. Abnormal conditions typically require corrective action by someone. I am not considering errors abnormal conditions since I consider errors, which are failures to accomplish goals through planned or unplanned action, to be different (and worthy of a separate post). Alarms, while not normal, are also not what I am calling abnormal conditions here because most organizations have defined procedures for responding to them. NOT responding to an alarm is an abnormal condition.

When people respond to abnormal conditions, they do so in two main ways:

They try to fix them with the resources they have at hand (consult the manual, ask a co-worker, or push buttons randomly-don’t laugh, this happens).

They tell someone in authority to get additional resources and alert them to the abnormality.

Either way, problems impact work either from the delay until help arrives or distracting workers from the other work they are supposed to do.

Repetition of abnormal conditions is an important signal about a process. Analyzing repetitive abnormal conditions can reveal flaws or failed assumptions that underly processes. Assumptions can be valid at one time and become invalid later, which is often revealed by audits. High Reliability Organizing (HRO) requires taking action on abnormal conditions to understand why they occur so as to mitigate or eliminate them. The dividing line between which abnormal conditions require analysis and action and those that can be fixed by frontline workers is an important part of the design for HRO. The criteria for documenting, informing, and requesting help may have to be reevaluated periodically, but is seldom done because people have so many other things to attend to for accomplishing the mission.

I consider anomalies to be different from abnormal conditions. Most abnormal conditions keep work from progressing until fixed. They can be ignored, but that is uncommon in more reliable organizations. An anomaly is an event or piece of data that falls outside the boundaries of a procedure or policy. For example, equipment that doesn’t work the way the operator expects, system initial conditions that don’t match the procedure, or something that “doesn’t look right.” Workers must decide if an unexpected result merits stopping work. If your organization lacks guidelines for making these decisions, you can be sure the workers will still decide. It just might not be what you want.

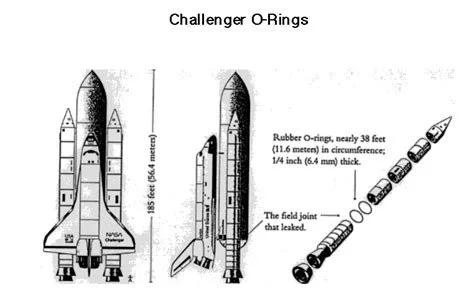

Anomalies are a clue about the existence of blind spots. An anomaly might repeatedly occur like Solid Rocker Booster secondary o-ring burn through (violation of a design criterion) or just once (weak signal) when something doesn’t happen the way a worker expects. Anomalies should be reported and possibly analyzed because they can reveal gaps in an organization’s assumptions, processes, training, or level of knowledge. Follow-up might reveal minor risks easily mitigated or a system vulnerability you never knew existed.

The second way blind spots can surface is through independent audits. “Independent” means audits conducted by people that aren’t the owners or users of the process. Sites that do HRO refer to this as “a fresh set of eyes.” Independence is an important attribute of audits because people with a lot of experience with the process have a tendency to see what they want to see because they use the process all the time. Secondly, process owners can be defensive when someone that works for them reports a problem. A process you don’t audit isn’t really a process because you have no idea what people actually do. I will have more to say about independent audits in the future.

Blind spots are as much an individual phenomenon as a group one. In any group of people, there is almost always someone that sees what others don’t either because they have a different perspective or have seen something others have not. Will they speak up about what they saw? Unless diverse or contrarian views are encouraged, supported, and carefully considered by managers, it is unlikely that any but the most courageous (or obstreperous) people will speak up. In organizations that lack support for speaking up, a really bad day is inevitable.

It can be unreasonable to expect people in the organization to speak up about problems and abnormal conditions no matter how much the leaders exhort them to do so. People’s practices in organizations are products of years of conditioning and experience, possibly from working at other places, and all the pleading in the world to report problems isn’t going to change what they have internalized from their experiences. This is why it is a good idea for leaders to walk around, talk to the frontline workers, and ask them what they’re seeing and what their concerns are.

Final Thoughts

The key idea behind this post is that you cannot manage blind spots, but you can teach workers the preferred ways to respond to indications that things are not quite right. First, by creating robust problem reporting and corrective action processes. This can give workers confidence that managers take their problems seriously and will do something about them. Second, have workers in one role (pharmacists for example) observe the work in other roles (nurses administering medication) to identify problems people are fixing without reporting or problems the pharmacists are creating for the nurses. Problems at the “sharp end” are inevitable without robust, cross-role communications. Workers there will “fix” them because they have to, but this leads to greater risk. Third, conduct independent process audits using repeatable procedures with requirements for process owners to respond in writing. Senior leader review of results and responses can provide deep insight into gaps in process assumptions and execution.

The intersection of blind spots and High Reliability Organizing (HRO) goes beyond requirements, practices, and procedures. High reliability leverages an organization’s system of mutually supporting roles and responsibilities to investigate blind spot indications, spread knowledge widely, and still allow people closest to the action (the “local environment”) flexibility to report problems and anomalies to system designers and managers (Bierly and Spender, 1995). HRO is a set of practices and communications that improves both blind spot detection and response.

* Bierly, P. E., & Spender, J. C. (1995). Culture and high reliability organizations: The case of the nuclear submarine. Journal of Management, 21(4), 639-656.